skip to main |

skip to sidebar

There are few clearer examples of the Cinema of Cruelty than Michael Haneke’s Funny Games. Ostensibly a tense, intricately-designed home invasion thriller, wherein a German nuclear family is terrorized by two young men, the film pokes, prods, and provokes via several choice breakings of the fourth wall. The killers appear, banter, and amorally control the cinematic universe. Mocking the conventions of backstory, hope, and justice, Funny Games entices the viewer with the standard psychological fare but confounds and chides at every turn, making the film an understandably frustrating experience. It’s a definite director’s movie, with the killers existing as direct agents of Haneke as well as commentators on the diegetic space itself, but in any case they are ultimately puppets at the hands of the filmmaker. They wink and ask questions of the camera, goading the viewer into continuing to watch despite knowing full well that no happy ending is on the horizon.

There are few clearer examples of the Cinema of Cruelty than Michael Haneke’s Funny Games. Ostensibly a tense, intricately-designed home invasion thriller, wherein a German nuclear family is terrorized by two young men, the film pokes, prods, and provokes via several choice breakings of the fourth wall. The killers appear, banter, and amorally control the cinematic universe. Mocking the conventions of backstory, hope, and justice, Funny Games entices the viewer with the standard psychological fare but confounds and chides at every turn, making the film an understandably frustrating experience. It’s a definite director’s movie, with the killers existing as direct agents of Haneke as well as commentators on the diegetic space itself, but in any case they are ultimately puppets at the hands of the filmmaker. They wink and ask questions of the camera, goading the viewer into continuing to watch despite knowing full well that no happy ending is on the horizon.

For all of its intensity, it remains remarkably restrained, with Haneke employing long takes and moving the camera away from several scenes of violence to force the viewer to confront what’s off-screen. It’s also telling that the bloodiest moment occurs to one of the killers, who are not human in the least. They can explode in blood, because Haneke has shown them to not be real. The victims, on the other hand, for all intents and purposes, are living things at the mercy of something more powerful and bloodthirsty than themselves, and their deaths are cruel and unjustified. They suffer, and they die, but Haneke is too canny and controlling to allow the viewer to get their rocks off by showing it. The camera even prudishly stays above the wife’s shoulders as the killers force her to strip; but when they leave and she must change in order to escape and find help outside the house’s grounds, her see-through bra reveals what the audience was secretly hoping to see. Only now, terror and exhaustion have sapped any exploitive pleasure that could have been had. Perhaps not every viewer is motivated by a lust or cruelty of their own, but merely a morbid fascination in seeing something through to the end; but Haneke doesn’t care why you stayed until the finale, only the fact that you did. You had the power to turn it off, you had the power, like the killers, to rewind the tape to the beginning and leave it at that. Haneke has planted clues throughout as to the invincibility of the killers. But you stayed.

If all of this sounds like Haneke is the master smacking the collective audience’s canine nose with a newspaper, maybe that’s because that’s kinda like what it is. Haneke’s assured and audacious control, especially in the briefly-mentioned rewinding scene, may alienate as many as it provokes. The fact that we as viewers are always at the mercy of the filmmaker’s godlike status is a not-so-minor corollary to the main thesis of the watcher’s culturally-inculcated insensitivity to violence, so that afterwards we may think twice about handing ourselves over to a movie. Its reflexivity walks a tightrope between asking the viewer to not take media at face value, and to investigate and reassess the effects media may have already made on us. Haneke and the film laugh in our face for playing their own set of “funny games,” but secretly they hope that they’ll never be able to do so again.

IMDb page

"I got poetry in me."

"I got poetry in me."

-McCabe & Mrs. Miller.

Sacha Baron Cohen’s series Da Ali G Show is a masterwork of unscripted guerrilla comedy, featuring Baron Cohen, disguised as one of three stereotyped personalities, interviewing various individuals and exposing their ignorance or prejudices in the process. While the British hip hop/Afro-Caribbean parody Ali G and the flamboyantly homosexual Austrian Bruno are effective in pushing cultural buttons, it is the English-mangling, anti-Semitic Kazakh journalist Bruno Sagdiyev that provides the most cutting, subversive laughs that catch in one’s throat. His eagerness to explore American culture and infectiously innocent enthusiasm make his unstaged interviews with politicians, preachers, and ordinary Americans the show’s constant highlights. In this vein, Baron Cohen has combined unwitting participation by regular citizens and the most tenuous of plotlines to craft a vulgar, illuminating, subversive, audaciously funny mockumentary.

Sacha Baron Cohen’s series Da Ali G Show is a masterwork of unscripted guerrilla comedy, featuring Baron Cohen, disguised as one of three stereotyped personalities, interviewing various individuals and exposing their ignorance or prejudices in the process. While the British hip hop/Afro-Caribbean parody Ali G and the flamboyantly homosexual Austrian Bruno are effective in pushing cultural buttons, it is the English-mangling, anti-Semitic Kazakh journalist Bruno Sagdiyev that provides the most cutting, subversive laughs that catch in one’s throat. His eagerness to explore American culture and infectiously innocent enthusiasm make his unstaged interviews with politicians, preachers, and ordinary Americans the show’s constant highlights. In this vein, Baron Cohen has combined unwitting participation by regular citizens and the most tenuous of plotlines to craft a vulgar, illuminating, subversive, audaciously funny mockumentary.

To dispense with the pretext, Borat concerns Mr. Sagdiyev and his producer Azamat embarking on a road trip across America to bring to Kazakhstan via documentary the wondrous world of the U.S. and A. Same shtick as Ali G with a connecting thread, basically. Each individual vignette is a thing of genius, though, sometimes pointing out the racist and bigoted views under the surface (a gun seller’s near-immediate answer to "Which gun would be best to defend from the Jews?") or the pure ignorance regarding a foreign culture (opening and closing segments set in Borat’s home village of “Kusek, Kazakhstan”). The “running of the Jew” and various gypsy epithets easily play into both a long-standing history of intolerance and stereotyped visions of Eastern European culture, but the examples are so blatant and skewed that to take them seriously is to play into them. In lesser hands, this social satire could have been dangerously misinterpreted as actual racism or cultural insensitivity (and indeed already has been by some uninformed or biased viewers), but one can imagine that a man with the education of Baron Cohen (whose thesis at Cambridge was on the Jewish presence within the American civil rights movement) knows exactly the political and social implications of what he says. Besides, the absurdity of Borat’s various interviews leaves no doubt as to the intentions. And despite the presence of Seinfeld writing alum Larry Charles as director, make no mistake that Baron Cohen is the comedic auteur behind Borat and the source of its intentions.

From the outset, Baron Cohen eschews the traditional realm of entirely joke-centric comedy for a relatively unexplored (and awkward, for the viewer as well as the victim) mix of miscommunication and revealing cultural conformity on the part of the interviewees. An early scene featuring Borat’s ruining of traditional joke forms while talking with some kind of “comedy consultant,” only puts forth Baron Cohen’s basic purpose of making the audience laugh in a new way, one that isn’t “clean” or “acceptable.” Not only is Borat’s misapprehension funny, but the consultant’s exasperation and, really, supposed authority in the subject are the real butts of the joke. Those who attempt to impart confident and dependable expertise in such freeform or, alternatively, socially-constricting areas as comedy, religion, or etiquette can become the most savaged targets of Cohen’s guerrilla tactics. Witness the cross-cutting between scenes of Borat being coached by an “etiquette advisor,” with the real fruits of the advisor’s teachings. After Borat is told to make honest compliments to fellow guests at an upscale Southern dinner, his insensitive (but “honest,” mind you) statements do nothing to endear him to his hosts. And yet the dinner continues to go on, leading to one of Baron Cohen’s most important and subversive satiric bullseyes: twofaced cultural “sensitivity” and conformity.

Upon researching the history of Baron Cohen’s use of Borat, it becomes apparent that, despite increased awareness by the public of Baron Cohen’s alter-ego, the method and success of these improvised comedy sketches has been amazingly consistent. Despite his modus operandi being unchanged over several years (obviously no real credentials, incredibly vague release forms), Baron Cohen has managed to fool a wide range of individuals without many serious repercussions. My hypothesis is that this stems from the paradoxically reactionary and tolerant mindset of modern America, the former providing the main artillery for Baron Cohen’s comedic assault and the latter effectively covering his retreat. Most of Borat’s interviewees feel this push-and-pull between indignity against his obviously narrow-minded statements, and leniency for his verbal “foreign” indiscretions. That a camera is present may help explain this phenomenon, as spontaneous street scenes reveal an American public scared of or openly hostile to odd foreigners; yet television personalities and interviewees usually forgive a great deal of intolerance by and awkwardness from the Kazakh interviewer until it becomes too much. In this light, Baron Cohen’s choosing of this country for his character’s home becomes ingenious. Mainstream America has no facts to draw up on regarding Kazakhstan, but it seems both vaguely Middle Eastern (this view is helped by Baron Cohen’s naturally-grown moustache) and culturally backward (thanks to Borat’s accent and customs) which feed into both sides of the aforementioned American mindset. As a catalyst for bringing out the worst in modern conservative and liberal attitudes, Borat is a carefully calculated and invaluable creation.

This all applies equally to Da Ali G Show and to Borat, so what can distinguish the two? As a narrative, the film’s road trip plotline enhances and detracts from the comedic thesis in turn. The driving action involves Borat trying to find Baywatch alum Pamela Anderson for “making sexy time” after watching her on a hotel television. Using such an obvious example of sexual objectification plays into Borat’s fascination with American culture while providing the pretext for two mordantly funny late scenes: having been dumped by his producer and left to hitchhiker, Borat finds a ride with three partying frat boys who show him Anderson’s infamous sex tape; and Borat stumbles upon a Pentecostal revival and is “shown the light.” Here again Cohen plays up the schizophrenic cultural values at work in American society by showing how muddled intentions and repercussions can be. Upon hearing Anderson’s name, the frat boys try to engage Borat in chauvinistic male bonding by popping in the sex tape, but they unwittingly deject him because he assumed she was a virgin. Likewise, the religious revival unknowingly provides Borat the boost to pick up his pursuit of sexual conquest. That the frat boys and church goers don’t care who you are on the inside as long as you're with them on the outside is their most damning quality. The masculine and religious mentalities convert and attempt to conform without imagining the internal consequences and Borat exploits this to the fullest.

The film’s comedic secret weapon is the character of Azamat, ably performed by the rotund and Armenian-American Ken Davitian. He has all of the vague “foreigner” baggage as Borat, but his presence amplifies his on-screen partner’s antics. It provides a potent counterpoint to Baron Cohen's tall, gangly frame, as evidence by already the most infamous and groundbreaking sequence in Borat: a protracted nude fight scene between the two in a posh hotel. As it spills from their single room to the hallway to an elevator to a crowded meeting in the ballroom, two things become clear: that Borat is transgressive as well as subversive, and that Baron Cohen, through Borat, can get away with anything. The image of Borat in flimsy spandex on the beach is common among the film’s advertising, but nothing preceding or on Da Ali G Show can prepare a viewer for the entwined, wrestling bodies of Baron Cohen and Davitian. It pushes the limits of traditional good taste while being so undeniably comical that an audience will probably be as awed as those watching two grown men in the nude, chasing each other down a hallway. For a mainstream studio film, let alone a comedy, to only provide unappealing male nudity to its viewers is, at the least, provocative and, at the most, firmly transgressive against the boundaries of audience expectations. The absurdity of the film’s situation reaches critical mass when the two men run through the hotel ballroom and interrupt a business meeting. Even if the hotel staff was in on the joke, it seems unlikely that every sitting businessperson knew what was going on, and in either case, Baron Cohen wields considerable power in his Borat persona. If security is not lax beyond belief, Borat can somehow convince the management to allow the scene to be filmed in public. The movie up to this point has only been goading its witting or unwitting participants; this sequence similarly unnerves (as well as entertains, which it has always done thus far) the audience. New viewers may find themselves watching through splayed fingers.

If the film goes wrong in any capacity, it is in its main conceit of being a “documentary.” Whereas someone watching This is Spinal Tap or Forgotten Silver without any prior knowledge of the cast or conceit could conceivably be swayed into mistaking it for the real thing, Borat has too many expansive shots of the two Kazakhs on the road or driving away from a scene to be misleading and possibly subversive to a first-time watcher. Whether certain scenes were staged or spontaneous in the end does not affect the comedic aesthetics of the film, but the narrative still suffers. Unlike someone such as, say, Andy Kaufman (to whom Baron Cohen is constantly compared), Baron Cohen lets his audience know they’re in on the joke and that there’s really a joke to be in on. This would seem to suggest that Baron Cohen could never reach the ultimate height of performance art that Kaufman ascended, but there’s hope in knowing that Baron Cohen always stays in character and that one is never sure if he’s taken a joke too far. But really, this lack of documentary realism is a mere quibble in comparison to the hilarious and inspiring whole that is Sacha Baron Cohen’s exploration of American values and cultural proclivities. While I have no doubt that audiences will find it funny as well as offensive, I fear that Americans will stop there and not realize that the joke is both for and on us.

IMDb page

War is hell. Calling a man a “hero” does not make him one. True heroes do not think of themselves as such. And, in the case of the WWII Marines in the world famous flag-raising photo of Iwo Jima, heroes are marketed, not made.

War is hell. Calling a man a “hero” does not make him one. True heroes do not think of themselves as such. And, in the case of the WWII Marines in the world famous flag-raising photo of Iwo Jima, heroes are marketed, not made.

All of these ideas are established by William Broyles, Jr.’s and Paul Haggis’s screenplay for Flags of Our Fathers, and then revisited…and revisited…and revisited. From a storytelling standpoint, the film leaves much to be desired; it awkwardly threads together three separate timeframes, one of which is barely filled out at all, and makes its themes evident from the beginning. The strongest complaints against Haggis’s previous screenplays for Million Dollar Baby and Crash concerned their thematic exposition and lack of subtlety, especially in terms of such wrenchingly complex issues as euthanasia and racism. Flags continues this trend, putting into the mouths of characters such explicit statements of thesis and moral that one whole plotline (a post-photograph publicity tour for war bonds) amounts to a hokey, protracted lecture on all three of these topics: war, ethics, and racism.

Again and again the soldiers deflect admiration from themselves to their dead comrades; the military and governmental leaders look corrupt and bloodthirsty for financing their own little war; and Native American Marine Ira Hayes (Adam Beach) is the butt of bigoted epithets, jokes, and cruelty, while actually exhibiting several of the traits for which he is stereotyped. Kudos for at least attempting to paint the leadership of the Pacific theater campaign as less than rosy, but it doesn’t help that those men are just as caricatured as the main figures. This is not even to mention the dessert-shaped-like-the-flag-raising scene, perhaps the most painfully obvious explanatory symbol in recent cinematic memory, only furthering the film as historical lecture rather than a living, breathing narrative. Not to mention that one of the Marines explicates the truth about the flag-raising photograph minutes before the scene itself unfolds more or less as described. Repetition and heavy-handedness dull the impact of what halfway interesting things Flags of Our Fathers actually does have to say regarding the establishment of heroic figures for national pride, at any cost.

Modern audiences may in fact recognize this sentiment more than a period audience would have. Instant celebrities (just add drama!) are a dime-a-dozen, especially ones who happened to be at the right place at the right time. The screenplay hammers this point home with the soldiers’ protestations, the most limelight-hungry Marine even conveniently deflecting praise at a crucial public gathering. The only difference between manmade celebrities then and now seems to be an acute psychological collision of national duty and physical horror that plays directly into the military’s hands. Despite learning to loathe the spotlight, the soldiers are still pressed forward both from within, by an understandable sense of honor mingled with regret for their comrades’ fates, and from without, despite (or because of?) the exaggerated money-hungry eyes of the military and political leaders. This interesting dichotomy is facilely presented but hardly investigated, elbowed out of the way by repeated motifs of the photograph in various forms and Ira Hayes getting drunk and sobbing. Basically, subtlety is not Flags of Our Fathers’ strong suit.

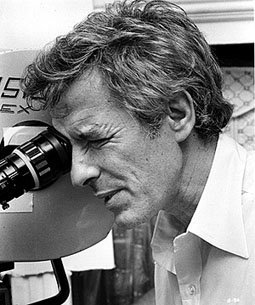

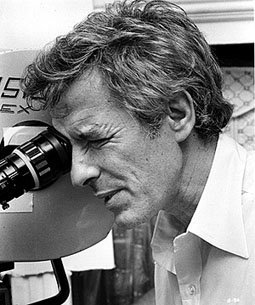

Intercut with these trite and prolonged events is the actual invasion of Iwo Jima, which, at times, almost makes one forget the rest of the film. Director Clint Eastwood, a modern yet classical workman like no other, stages the battle with violent immediacy that clearly recalls Saving Private Ryan, directed by Flags’ co-producer Steven Spielberg. Looking even further into the past, Eastwood hearkens back to black-and-white newsreel footage with washed-out colors and desaturation, lending the film an authenticity if not a realistic look. It gels with what World War II has been shown to look like in previous films and on television. No matter how many battle scenes are staged, however, there is still a visceral gut-punch that accompanies the slaughter of GIs on a beach, whether you know that the entrails and severed limbs are artificial or not. The film works well here, where “war is hell” can be seen and heard, not merely said. It permeates the machine gun sounds, the frenzied cries of servicemen charging and retreating. Even from this point, Flags is hardly groundbreaking stuff, but Eastwood the stylist produces a nonetheless compelling portrait of men dwarfed by combat on a world scale, where facelessness is the nature of the beast. That’s why the best moment in the film, the probable mutilation and murder of a young Marine discovered by a friend, is silent and not shown, even when the aftermaths of grenades and bullet wounds are on display. It is a testament to the unspeakable character of warfare, even in as seemingly justified a context as World War II. It touches a deeper nerve than Haggis’s and Broyles’s telegraphed speeches about “dying for my country” and “we weren’t the real heroes.”

Eastwood puts little political commentary into these battles, save some unsettling shots from the points of view of the Japanese pillboxes, perhaps anticipating his companion piece, Letters from Iwo Jima. Here’s hoping that that film can create interesting characters and investigate its subject, rather than belabor its ideas with hackneyed exposition and rudimentary symbol.

IMDb page

It takes a deft hand to craft a children’s film without alienating a mature audience or simply resorting to visual and aural stimuli for 90 minutes. Children may not understand the implications or dimensions of a complex narrative, but adults, presumably, can remember when they were children; so the best children’s films have always appealed to both groups by tapping into a rich vein of imagination and basic emotions. The career of Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki (and his production company Studio Ghibli) has been built on this principle, and his mastery of visuals, fantasy, and childlike wonderment, is in perfect evidence in My Neighbor Totoro.

It takes a deft hand to craft a children’s film without alienating a mature audience or simply resorting to visual and aural stimuli for 90 minutes. Children may not understand the implications or dimensions of a complex narrative, but adults, presumably, can remember when they were children; so the best children’s films have always appealed to both groups by tapping into a rich vein of imagination and basic emotions. The career of Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki (and his production company Studio Ghibli) has been built on this principle, and his mastery of visuals, fantasy, and childlike wonderment, is in perfect evidence in My Neighbor Totoro.

Totoro begins with the arrival of young, bright sisters Satsuki and Mei (voiced by Noriko Hidaka and Chika Sakamoto) and their father into a country village to be closer to their hospitalized mother. The girls’ charming liveliness, especially in the face of dislocation, initially betrays any fear they may have. Even the father is admirably cheerful during the move, and he plays along with the girls as they claim to see ghostly soot in their rickety new home. It remains unclear how much the adults of the film believe in the fantastic (but unseen) events that later take place, but they have no desire to spoil the imaginations of their young ones. The mother’s illness lies just at the edge of their awareness when there’s a new place to be explored. The film perfectly encapsulates a time of life between willful freedom and a semblance of responsibility, without sacrificing a child’s awe at the surrounding world.

The movie is “wide-eyed,” like its adorable protagonists, and “crouching,” like the father following his daughters into the forest; it is literally and symbolically told from a child’s point of view. As the girls wander, the film takes in the lovingly detailed scenery from the ground up, and the camera’s graceful tilts and pans absorb trees, water, and everyday creatures of the forest. Mei, being the youngest, naturally stumbles upon the magic of nature first. She spots small, furry, bulbous creatures scurrying a garden for acorns, and her pursuit leads to a monumental discovery: the innocent, massive, sleeping creature Mei dubs “Totoro,” for a mispronunciation of the Japanese word for “troll.” Totoro seem to be some kind of a cross between a koala, a bear, and a cat, but its magic lies in its uniqueness. Despite its imposing girth, Mei immediately connects with a profound sense of communion and friendship. These children have thankfully not yet learned to fear the unknown. Totoro provides a comforting presence when the mother’s illness begins to loom in the children’s world.

Even though Mei is the first to experience the fantastic, it is Satsuki who proves to be the film’s protagonist. Despite being pre-teen and seemingly as carefree as her little sister, her situation thrusts duty and awareness upon her. It’s no surprise that Satsuki notices the magic around her when their father is late and Mei takes comfort on her back; she is becoming a surrogate mother for her sister (and an adult) by taking the first steps of responsibility. Her key to straddling the worlds of childhood and adulthood lies in the wonder of the forest, and her own imagination. Initially, she keeps her roles as sister and young girl separate, until Mei’s appearance at her school prevents this division. With the younger sister’s wild drawings and enthusiasm, Satsuki is understandably embarrassed. It takes a strange but wondrous encounter with Totoro for Satsuki to appreciate her sister’s ravings; and when Mei is missing, Satsuki discovers an adult responsibility, also by communing with the forest’s creatures. Her ability to be both an adult and a child comes directly from her imagination, a stereotypically childlike trait that need not be thought of as such.

Just as Satsuki is two things at once, the village is a magical synthesis of fantasy and fact, nature and technology. The most famous example of this is the Cheshire-like catbus, as literal a name as could be imagined. With a wide grin, furry outside, and warm, comfortable inside, it merges a reassuring, innocuous house pet with a modern transportation vehicle. Its first appearance, in conjunction with Totoro’s discovery of umbrellas courtesy of Satsuki (another meeting of natural being with modern technology), is delightfully unexpected and odd. Even the children, who recognize Totoro as harmless, appear nonplussed. Despite using a framework designed by man as machinery, the catbus flies and transforms as only something enchanted can do. There’s also a nice ecological undercurrent running through My Neighbor Totoro, especially during scenes of Mei and Satsuki planting acorns, but it never becomes saccharine or preachy, nor does it posit humanity as encroaching on the natural order of things. The forest inhabitants seem just as content as the serene residents of the village. Every animal or insect depicted in the film, whether realistically or fantastically, has its place and respect within the forest world.

Above all, the film eschews antagonism and conflict for astonishment and whimsy. There is no “us against them” connotation to the girls’ relationship with their father or with any other adults. Too many children’s movies paint grown-ups as naturally in opposition to children, or pander to a literally childish attitude. Perhaps this is sidestepped by the Japanese ideal of generational unity shown in the film. Children and adults, especially in a village without modern culture, are hardly at odds. In addition, Mei and Satsuki are regular kids, but their reactions to experiences are universal. There is even a shy boy, Kanta, in case young male viewers need someone to recognize. He gradually learns to accept his new neighbors and eventually provides shelter and assistance to the girls in need. With adults in the lead roles, Totoro would surely turn into a different movie, but it hardly takes a giant leap for someone of any age to identify with the sisters’ astonishment at discovering the supernatural or terror at being separated and far from familiarity. That oft-used phrase “inner child” could accurately describe the target of Miyazaki’s cinematic power. His images and sensibility strike at a deep, collective well of emotions that are considered childlike; but his message is that an understanding and embracing of these feelings, all too commonly lost in the rush of adulthood, lead to richer, warmer, even more fanciful lives.

IMDb page

The message of Oliver Stone’s film of two Port Authority police officers trapped in the rubble of the World Trade Center towers is summed up in its epilogue; there is little to no subtlety or character development to be found; and the subplots are saccharine, melodramatic, or altogether unnecessary. And none of this really matters.

The message of Oliver Stone’s film of two Port Authority police officers trapped in the rubble of the World Trade Center towers is summed up in its epilogue; there is little to no subtlety or character development to be found; and the subplots are saccharine, melodramatic, or altogether unnecessary. And none of this really matters.

What does matter is the simple earnestness in the performances of Nicolas Cage and Michael Pena as McLouglin and Jimeno; the brutal claustrophobia that engulfs any scene within the mangled wreckage; and the stark desperation from Maria Bello and Maggie Gyllenhaal as the wives. The film begins simply enough with an ordinary day for the Port Authority police and New York City in general. Friends joke, cars in traffic honk, officers walk their beats. Once the terrible tragedy occurs (tactfully off-screen), the world becomes black and white, and there is no room for subtlety. The main characters are thrown into a confused rush of victims, bystanders, rescuers, policemen, firemen…the anarchy that resulted from the devastating attack. Their objective is to help out, but before they really can, one of the towers and the entire world collapse around them. Harrowing is the only word for it. World Trade Center is both the loudest and quietest film of the year thus far. The sound design rains destruction and chaos throughout the theater. Screams and anguish flood the tiny open spaces between hunks of twisted wreckage and concrete rubble. Despondency sets in quickly, and McLoughlin and Jimeno make a grave pact to see each other through the calamity. Their helplessly quiet dialogue and struggle to keep conscious are the restrained, human responses to their apocalyptic scenario.

It is here that the main thrust of the film, the parallel stories of the two officers and their families, begins. To call these segments “sentimentalized” or “Hollywoodized” is to miss the straightforward, apolitical impact of the film. The worst has happened, and the families must react. Both families have several children, and one wife is pregnant. Reality provides and transcends clichés. As Maria Bello walks around her house practically in a daze, she imagines her husband fixing the roof, or teaching their son how to do carpentry. Both men hear their wives’ voices and imagine seeing them. Overwrought? Formulaic? Perhaps. But what are they all supposed to be thinking about? I had no direct relation to the tragedy, but during that entire day, every moment that I was not intensely focused on something else, I thought about what had happened. A particularly effective scene in this vein focuses on Gyllenhaal suddenly realizing the banality of shopping in a drug store. Each of these moments felt just about or beyond poignant, perhaps even overtly melodramatic, but life, especially in light of the universality of this event, need not apologize for its inherent drama.

When the film reaches beyond the two men or their immediate families, it falters. A patriotic and religious former Marine (Michael Shannon) seems to symbolize the men and women who signed up following September 11, but his inhuman and emotionless passivity towards duty makes him less than sympathetic. A bizarre vision by Jimeno of Jesus with a water bottle is head-scratching rather than realistically “stranger than fiction.”

But these instances do not take away from the obvious, heartfelt power of all involved, even the otherwise controversial and political Oliver Stone. He (and screenwriter Andrea Berloff) is not out to tell every story of that day, nor to cover its implications, nor to whitewash the catastrophe of that day. His subjective focus on two families’ near tragedy is traumatic but ultimately hopeful that courage and dignity can inspire hope even in the face of such a disaster. Too soon? Hardly. Too sentimental? A film like this could not be.

IMDb page

The only similarity between the mid-‘80s series “Miami Vice” and its cinematic counterpart is the criticism-turned-credo “style over substance.” But whereas the TV show at least had sunny locales, hip music, and the pastel presences of Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas, Michael Mann’s re-imagined Miami Vice is mired in an incoherent plot, lifeless performances, and outrageous violence covering up for missing dramatic and thematic content.

The only similarity between the mid-‘80s series “Miami Vice” and its cinematic counterpart is the criticism-turned-credo “style over substance.” But whereas the TV show at least had sunny locales, hip music, and the pastel presences of Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas, Michael Mann’s re-imagined Miami Vice is mired in an incoherent plot, lifeless performances, and outrageous violence covering up for missing dramatic and thematic content.

Colin Farrell and Jamie Foxx take over the mantles of “Sonny” Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs with nary a wink or a smile. Never before has either actor been so patently glum or bored. Mann has had success in the past encircling his films around a dangerous, lone wolf figure stalking the modern urban jungle (James Cann in Thief, Robert DeNiro in Heat, Tom Cruise in Collateral), but neither Farrell nor Foxx have the dangerous charisma (or requisite three-dimensional characters) to pull this off. Half-baked girlfriend subplots involving Naomie Harris and Gong Li do nothing to elevate the two heroes above caricatures of cops whose work is their world. The love that blossoms between Farrell and Li especially strains credibility. Am I to believe that this beautiful and savvy businesswoman married to the boss of a Columbian cartel would then be wooed by a stubbly Irish-American thug?

Crockett and Tubbs eventually go undercover to catch the drug smugglers and investigate a mole in the crime squad (a plot thread that is never even resolved), and main villains Luis Tosar and John Ortiz breathe a bit of life into the proceedings. But their nefariousness is constantly undermined by wasted “emotional” scenes between Farrell and Li, and some muddled police procedure that leads to an absurd conclusion. For all of the far-fetched plot twists in Mann’s previous films, they were nearly always involving interesting characters and bravura action sequences. Vice delivers more violence than action, the splattering of red fluids being the only source of bright colors in the movie’s monochromatic world. Once Crockett and Tubbs’ fellow task force agents show up and prove to be handy marksmen, any tension as to the fate of our heroes quickly disappears. Most of Mann’s strengths (masculine characterizations, ferocious and exciting gunplay) become burdensome.

The only spark is provided by Dion Beebe’s HD digital cinematography. The high contrast that brought LA into light and shadow in Collateral turns Miami into a bustling backdrop of blue-gray. The camera searches and hunts for an interesting shot, whether or not that goal is reached. Valiant attempts to render the film compelling only on the surface are futile from the beginning. Hopefully Mann can let sleeping ‘80s cop shows lie and spend more time overcoming this artistic hurdle. I have complete faith he can do it.

IMDb page

There’s a central mystery in Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract, one that’s existence is only gradually revealed and with clues literally lying around; but whether this mystery need be solved is another question entirely. Beyond the mere twists and turns of the Restoration-era setting and plot lies Greenaway’s fascinating formality of images, archly elevated dialogue, and ultimate destruction of his character’s egotistic personality.

There’s a central mystery in Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract, one that’s existence is only gradually revealed and with clues literally lying around; but whether this mystery need be solved is another question entirely. Beyond the mere twists and turns of the Restoration-era setting and plot lies Greenaway’s fascinating formality of images, archly elevated dialogue, and ultimate destruction of his character’s egotistic personality.

In the late 1600s, Neville (Anthony Higgins) is a draughtsman who agrees to make twelve drawings of the Herbert Estate for Virginia Herbert’s (Janet Suzman) absent husband. The trick in the contract involves various sexual payments by Mrs. Herbert. As the drawings are being constructed, Neville enters into a similar contract with Herbert’s married but loveless daughter (Anne-Louise Lambert). Neville begins noticing peculiarities with the layout of the estate and of miscellaneous objects being left outside. He becomes increasingly involved with the politics of the Herbert estate until Mr. Herbert himself turns up missing with Neville as a prime suspect.

Few characters I’ve encountered are as acerbically confident as Neville. He boasts of visual perfection, and the gall of establishing the contract in the first place is revealing. He seems especially to enjoy casual control over Mrs. Herbert, organizing their sexual rendezvous with little secrecy and much triviality. Anthony Higgins anchors the performance aspect of the film, delivering the funny but complex dialogue with panache and even at times, genial menace.

However, Greenaway is the one in control at all times. His eye for composition and the mostly static cinematography lends the film an exquisite, painterly beauty that goes against the period intrigue and dialogue. But this conflict only puts more focus on the scenery, especially in comparison to Neville’s drawings. A major motif is the use of a grid that allows the draughtsman to draw more easily. Neville thinks he can achieve perfection through his craft, in recording everything he sees in its proper place. This proves impossible; what he sees is (unbeknownst to him) damning, and he cannot separate his affair with Mrs. Herbert and the more artistic aspects of his contract. Greenaway is thus toying with his central character, just as the unfolding of the plot and lack of true resolution toy with the audience’s expectations. Apparently a three-hour version of The Draughtsman’s Contract exists, and it explains in depth the more puzzling and oblique plot points, characters, and scenes. But ultimately, the film needs an air of mystery to complement the director’s potent images and the ruin of his protagonist’s delusions of perfection.

IMDb page

The unassuming grace of Ermanno Olmi’s early ‘60s feature, Il Posto (The Job), becomes even more apparent in the era of high concepts, expensive stars, and special effects. Employing amateurs and real citizens as extras, as well as filming in only actual locations, Olmi was able to elicit natural (not naturalistic) performances and involve the viewer in everyday life and struggles. If this concept seems slight or dull, especially when used to highlight a young man’s entry into a Kafkaesque office workforce, it is Olmi’s use of space and editing that imbues realism with the substance of art.

The unassuming grace of Ermanno Olmi’s early ‘60s feature, Il Posto (The Job), becomes even more apparent in the era of high concepts, expensive stars, and special effects. Employing amateurs and real citizens as extras, as well as filming in only actual locations, Olmi was able to elicit natural (not naturalistic) performances and involve the viewer in everyday life and struggles. If this concept seems slight or dull, especially when used to highlight a young man’s entry into a Kafkaesque office workforce, it is Olmi’s use of space and editing that imbues realism with the substance of art.

Il Posto is unabashedly autobiographical but strongly universal. It tells the story of Domenico (Sandro Panseri), a soulfully sad Italian youth from the suburbs applying for a big city career. He is subjected to simple psychological, physical, and mathematical exams, yet is degraded by literally competing beside a host of applicants of varying ages and expressions. The only saving grace is the presence of pretty Antonietta (Loredana Detto), the only other applicant of Domenico’s age group. She’s bright and assured where he’s uncertain and reticent. Olmi counterpoints their quietly budding relationship with the cul-de-sac existence of the office workers. While the employees have been hammered over the years into finding the office building as their primary place of life and existence, Domenico sees Antonietta as a new opportunity brought by the job. When they are separated by differing departments, Domenico, now an assistant mail worker, still tries to find chances to meet her. A New Year’s office party proves fruitless in his quest to make more of their relationship, but he still finds fun and excitement, however minor and short-lived, among his fellow drones. A clerk dies soon after, and Domenico obtains this position, providing an ambiguous end to the film and beginning to his office life.

Olmi’s strengths as a filmmaker lie in realism, performance, and sympathy. A true humanist, he finds the strengths and weaknesses of his characters as facets in the same raw gem. His cuts between the faces of Domenico and Antonietta, greatly enhanced by the unpolished beauty of Panseri and Detto, reveal more about their personalities than any number of pages of dialogue ever could. The darting of eyes, the pursing of lips...it is these facial tics that show the true nature of human beings, and Olmi captures them without force or urgency. But the director is not simply about close-ups; he also frames the crowded applicants like cattle in a pen, or a lone clerk engulfed by spacious, labyrinthine hallways. For all of the inherent social and economic commentary, there is much more importance weighted on people, relationships, and community. This is where Ermanno Olmi’s true allegiance and interests lie, not with observations only on the sordid state of the postwar world, but in the simple, uncertain, yet undeniably dramatic lives of everyday citizens.

IMDb page

Even though it's about as Russian as Casablanca, Josef von Sternberg's masterful The Scarlet Empress eschews plot and dialogue for pure visual splendor. If the term "poetry" can be applied to visual images as well as to the written word, von Sternberg's film would most definitely warrant the label.

Even though it's about as Russian as Casablanca, Josef von Sternberg's masterful The Scarlet Empress eschews plot and dialogue for pure visual splendor. If the term "poetry" can be applied to visual images as well as to the written word, von Sternberg's film would most definitely warrant the label.

Using the story of German princess Sophia's transformation into Catherine the Great (von Sternberg muse Marlene Dietrich) of Russia as a starting off point, von Sternberg uses light, shade, and gothic imagery to convey the decadence and decay of Russia and Catherine's morality as her reign continues. All of these elements tensely build up the drama of the Russian Empire mostly without the aid of dialogue or intertitles. Brilliantly edited torture sequences bookend the story, once coming out of young Sophia's book and then happening for real under her creepily conniving husband, Peter (Sam Jaffe). The grandly extravagant and horrific set design trap every character in myth and romanticism, but these elements do not pierce the granite outsides of Catherine, Peter, or the Empress before them (a darkly comic Louise Dresser). Von Sternberg orchestrates not only the mise-en-scene to fit his vision but wrote and conducted the perfectly pompous music as well.

The performances, especially by Dietrich as naive princess and iron-fisted empress, are solid if the dialogue seems fit for a different setting (perhaps a light gangster flick). The film is less a history lesson than a magnificent exercise in style. To wit, an amazingly captured sequence featuring a gold pendant from one of Catherine's suitors encapsulates the physical rise and moral fall of the Scarlet Empress: Catherine tosses it out of a window onto a tree, and it falls from branch to branch, again and again, edited into a free-flowing cascade of beautiful collapse.

IMDb page

As a long-time fan of Garrison Keillor's sophisticated anachronism of a variety radio show, "A Prairie Home Companion," I found that the film adaptation preserves the spirit if not the letter of the program. Full of country/gospel music and a stellar cast, not to mention the fluid direction of Robert Altman, Prairie mixes myth and fantasy (which is the radio show's stock and trade) with realistic backstage antics during the program's final broadcast.

As a long-time fan of Garrison Keillor's sophisticated anachronism of a variety radio show, "A Prairie Home Companion," I found that the film adaptation preserves the spirit if not the letter of the program. Full of country/gospel music and a stellar cast, not to mention the fluid direction of Robert Altman, Prairie mixes myth and fantasy (which is the radio show's stock and trade) with realistic backstage antics during the program's final broadcast.

Keillor's screenplay and performance are folksy and whimsical, but not without hints of dark humor and contemplation. "G.K.'s" refusal to face his show's demise, or even the actual death of a musical regular, belies both a breezy callousness and a deep understanding of the cliche, "the show must go on." He seems to be the most professional and least bothered amidst the whirlwind of characters and backstage intrigue. Only briefly hinted at is his history with one of a pair of singing sisters, Yolanda Johnson (the standout Meryl Streep), who perform a duet that develops the characters as much as a any monologue or scene could.

Music plays a huge part in the film, perhaps even moreso than on the radio show, connecting it thematically with Altman's previous masterpiece of country, Nashville; except where that film's characters hid their true selves through jingoistic marches or ballads dripping with false emotion, the performers of A Prairie Home Companion open up and bare themselves in collective or individual celebrations of an old-fashioned musical form.

This isn't to suggest the film is all musical numbers and sentimentalism. Tempering the celebration of a lost art form (live radio variety) are supernatural occurrences revolving around a Dangerous Woman (the luminous, but slightly sleepwalking Virginia Madsen); the depressing daughter of Yolanda, Lola (Lindsay Lohan); the bawdy cowpokes Dusty and Lefty (John C. Reilly and Woody Harrelson); and the Clouseau-esque security chief Guy Noir (Kevin Kline). The final three characters are adapted from the radio program, but beyond their very basic descriptions, there's not much similarity. Each character provides atmosphere and levity while contributing to the anachronistic set of radio personalities. Some of the famous elements of the radio program, including Keillor's famous monologue about his fictional hometown of Lake Wobegon, are sadly missing or only appear in fragments. Both the director and screenwriter's works are acquired tastes, so neither is attempting to convert those who haven't or are unwilling to hear the show.

Robert Altman provides his signature visual sense that gels perfectly with Keillor's screenplay's knack for juggling multiple storyline threads. I found no one to be entirely the focus, but that the show itself was allowed to be the centerpiece. The camera expertly navigates through the hallways and crevices of the studio, jostling past crew members and catching multiple, unrelated characters in the frame together (especially with the Dangerous Woman lurking about). With Altman's aging and revelation about a heart transplant, the film's preoccupation with death can be contributed as much to the director as to the screenwriter. It seems as much Altman's baby as it does Keillor's.

The film met my expectations for both Altman and "A Prairie Home." It was sweet, funny, deceptively sad, comforting, and a good deal rambling. It accepts the end of an era without any maudliness or fake tears. Having "silence on the radio" is just a phase, because you can always switch to another station.

IMDb page

Andrei Tarkovsky's diploma short film, Katok i skripka (The Steamroller and the Violin), is a heartfelt and visually-impressive melding of fantasy and realism. Seven-year-old Sasha (an affecting young Igor Fomchenko) is a boy ridiculed in his neighborhood for playing violin. The opening sequence follows him as he hides from bullies and gradually makes his way to his lesson, where fear of adult authority mixes with puppy love regarding another music student. On his way home, Sasha is saved from more bullying by construction worker Sergey (a lightly macho Vladimir Zamansky). Sergey takes the boy on an eye-opening journey through the lower class streets. Sasha learns to defend himself and protect those smaller than him, and he brightens while watching and hearing the melody of a building being demolished. Sasha wants to see a movie with Sergey later that evening, but Sasha's overbearing single mother thwarts his plans. Sergey goes to the movies with a girlfriend, and Sasha sits in his room, contemplating escape on a steamroller.

Andrei Tarkovsky's diploma short film, Katok i skripka (The Steamroller and the Violin), is a heartfelt and visually-impressive melding of fantasy and realism. Seven-year-old Sasha (an affecting young Igor Fomchenko) is a boy ridiculed in his neighborhood for playing violin. The opening sequence follows him as he hides from bullies and gradually makes his way to his lesson, where fear of adult authority mixes with puppy love regarding another music student. On his way home, Sasha is saved from more bullying by construction worker Sergey (a lightly macho Vladimir Zamansky). Sergey takes the boy on an eye-opening journey through the lower class streets. Sasha learns to defend himself and protect those smaller than him, and he brightens while watching and hearing the melody of a building being demolished. Sasha wants to see a movie with Sergey later that evening, but Sasha's overbearing single mother thwarts his plans. Sergey goes to the movies with a girlfriend, and Sasha sits in his room, contemplating escape on a steamroller.

Tarkovsky's 50-minute slice of life avoids the trappings of childhood films with naturalistic performances and a unique visual sense. Mirrors and reflections in water show Sasha and Sergey new dimensions of their chosen fields, as each character reassesses the worth of his life. Sasha is in awe of the sound and power of Sergey's vehicle, while the soothing tenor of Sasha's violin seems to bring harmony, if but for an instant, to Sergey's world. It is amazing how much depth the film contains in such a short span of time. The conclusion, a powerful flight of fancy by Sasha, is a capstone to his dream of wish fulfillment on his own terms, whether with a violin, on a steamroller, or both.

"The Steamroller and the Violin" IMDb page

"Love, or the lack of it."

"Love, or the lack of it."

These few words encompass the only topics John Cassavetes ever wanted to tackle in his directorial career. Charles Kiselyak's A Constant Forge examines the filmmaker's career (from 1959's Shadows to 1984's Love Streams) and amounts to a marvelous, heartfelt love letter by fans, friends, and colleagues.

Few directors elicit such strong emotional responses from audiences as Cassavetes. His films attempt to go beyond the surface of human relationships, prodding and provoking the characters, and, as John hoped, the audience, into self-reflection and change. This is part of what good art always tries to do, but his method of presenting the true fragility of emotions and of man's understanding of himself and his environment, proved far too weighty and touchy a subject for most moviegoers and executives. Luckily his work never required huge amounts of funds, because filming people is much cheaper than filming things or locations. And people, and characters, was all that Cassavetes was interested in.

A Constant Forge is an insightful and quick 3 1/2 hours of the man's own words, film clips, and interviews with loved ones and acquaintances. After a brief look at each of Cassavetes's major directorial works, the film meanders through each phase and aspect of his career, from his early childhood and theater work to teaching acting to writing and directing. His assembled stable of reliable actors, including wife Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara, and Seymour Cassell, are all on hand to provide anecdotes and as much insight as they can to the man they all loved and respected. Falk is especially adept at providing quotes, including that John was "the most fervent man I ever met." Mostly, though, the clearest path to understanding the filmmaker as an individual is to listen to the man himself and watch his films. Cassavetes was, and is, his films.

I'm still not sure why I respond so well to Cassavetes's work. The emotional nakedness, even with the understanding of the tight script and prowess of the actors onscreen, frightens as much as it fascinates. No one was more interested in people or feelings than Cassavetes; hurtful and glowing emotions were of equal weight and worth in his lens. Apparently the man himself was less gloomy and moody than his output would suggest, even though the basis of his work was internal and personal. His stature as a true artist in a medium full of phonies, and even some talented charlatans, seems assured. He tried what no one else did, and whether he succeeded or not, he should be constantly commended. And A Constant Forge provides a solid background to his life and work whether you are a neophyte, a fence-straddler, a lifelong Cassavetes fan, or wondering what all the fuss is about.

"A Constant Forge" IMDb pageCriterion Collection page

After this long, loving the quirky stylings of John Linnell and John Flansburgh (collectively known as They Might Be Giants) may seem like a mere phase, the briefly pseudo-intellectual, wry posturing that results from outgrowing adolescence. To others, TMBG's minimalist and fiercely independent aesthetic, lyrically and musically, continue to point toward a utopia of ideas never before heard. Very few find themselves in the middle.

After this long, loving the quirky stylings of John Linnell and John Flansburgh (collectively known as They Might Be Giants) may seem like a mere phase, the briefly pseudo-intellectual, wry posturing that results from outgrowing adolescence. To others, TMBG's minimalist and fiercely independent aesthetic, lyrically and musically, continue to point toward a utopia of ideas never before heard. Very few find themselves in the middle.

Director A.J. Schnack's documentary of the band's members and influence may not exactly convert the uninitiated, but it has enough talking heads to provide a fun portrait of two unique musicians. Certains aspects of their live performances and infamous marketing techniques (the fascinatingly prolific Dial-a-Song) get explained by the men themselves and by some of their ardent celebrity and industry admirers. Some simply don't understand the infinite possibilities of the Two Johns' work, the experimentation and abstractly literate songwriting. The film attempts to demystify the band a little, but it's really just a fan-flick love letter.

The film appeared on the Sundance Channel earlier today. I became a Giants fan earlier than most; before I was a teenager I had worn out a cassette of 1990's Flood, and it even became the soothing soundtrack to any dental appointments during '92-'93. I've never seen them live, or investigated them as individuals. I've always only had the music, the Birdhouse in My Soul or the Hotel Detective, and that's more than enough. Thanks, John, and thanks, John.

"Gigantic (A Tale of Two Johns)" IMDb page