- The classic movie moment everyone loves except me is: None I can think of, honestly. Until someone starts talking about it, I rarely think of aspects of movies I dislike.

- Favorite line of dialogue from a film noir

- Second favorite Hal Ashby film Bound for Glory, one of his more subdued ones.

- Describe the moment when you first realized movies were directed as opposed to simply pieced together anonymously. Probably the pitch-perfect use of "The Blue Danube" in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

- Favorite film book I did a Next Projection list on this topic, and I'm sticking by The Material Ghost by Gilberto Perez.

- Diana Sands or Vonetta McGee?

- Most egregious gap in your viewing of films made in the past 10 years Even after all the #Team hoopla, I still haven't caught up with Kenneth Lonergan's Margaret.

- Favorite line of dialogue from a comedy A tie between Groucho's "Why a four-year-old child could understand this report. Run out and find me a four-year-old child, I can't make head or tail out of it" from Duck Soup, and Bill Murray's "Yes it's true, this man has no dick" from Ghostbusters.

- Second favorite Lloyd Bacon film It Happens Every Spring, one of my dad's favorites.

- Richard Burton or Roger Livesey? The Archers cannot be denied, so Roger.

- Is there a movie you staunchly refuse to consider seeing? If so, why? Nope, and that stance has caused many a worthless viewing.

- Favorite filmmaker collaboration

- Most recently viewed movie on DVD/Blu-ray/theatrical? In the theater, Soderbergh's Side Effects; otherwise, Bergman's Summer Interlude via Criterion's DVD.

- Favorite line of dialogue from a horror movie "He has his father's eyes." - Roman Castevet (Sidney Blackmer), Rosemary's Baby.

- Second favorite Oliver Stone film Talk Radio, I suppose.

- Eva Mendes or Raquel Welch? At the risk of offending the star of Bedazzled, Myra Breckenridge, and Mother, Jugs, & Speed I have to say the Eva Mendes of We Own the Night, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, and Holy Motors.

- Favorite religious satire

- Best Internet movie argument? For someone whose main hobby appears to be arguing movies over the Internet, you'd think I'd have a ready answer for this, but I don't.

- Most pointless Internet movie argument? Art vs. entertainment; as with most of these questions, the answer is both.

- Charles McGraw or Robert Ryan? Robert Ryan is an axiom of the cinema, while Charles McGraw is merely a really good part of an equation.

- Favorite line of dialogue from a western "We'll find 'em, just as sure as the turnin' of the earth." - Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), The Searchers.

- Second favorite Roy Del Ruth film Lady Killer, after Blonde Crazy.

- Relatively unknown film or filmmaker you’d most eagerly proselytize for

- Ewan McGregor or Gerard Butler? Is this even a question? Ewan.

- Is there such a thing as a perfect movie? No matter what the local Filmically Perfect hosts think, I don't believe so.

- Favorite movie location you’ve most recently had the occasion to actually visit I don't get to travel too much, so N/A on this one.

- Second favorite Delmer Daves film 3:10 to Yuma, after Dark Passage.

- Name the one DVD commentary you wish you could hear that, for whatever reason, doesn't actually exist Chaplin and Keaton talking over each other and over Limelight.

- Gloria Grahame or Marie Windsor?

- Name a filmmaker who never really lived up to the potential suggested by their early acclaim or success Most recently David Gordon Green, but there's still time; otherwise, I haven't seen the George Lucas of THX-1138 or American Graffiti in a long time.

- Is there a movie-based disagreement serious enough that it might cause you to reevaluate the basis of a romantic relationship or a friendship? I don't like to think so (it hasn't happened yet); as long as there is any other topic we can agree on, I can live with a disconnect in taste.

"All that Cain did to Abel was murder him." - Leo Morse (Thomas Gomez), Force of Evil.

Incidentally, my third favorite Hal Ashby film is The Landlord, so I'll pick Diana Sands.

If it's a directing duo we're talking about, then the Archers, a.k.a. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger; if it's some other duo, I also did a list on this topic and ended up with Kurosawa and Mifune.

The entire oeuvre of Luis Buñuel.

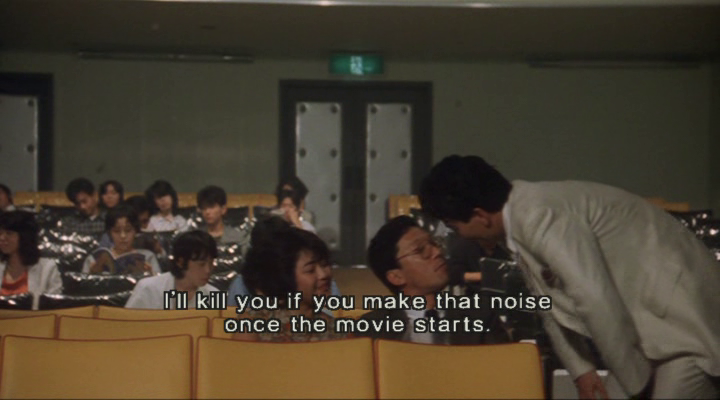

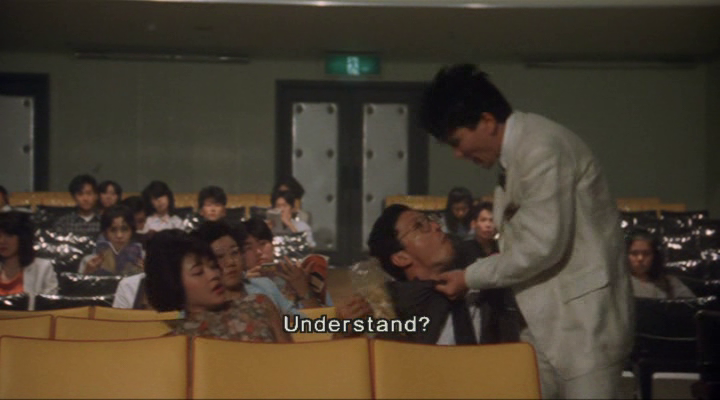

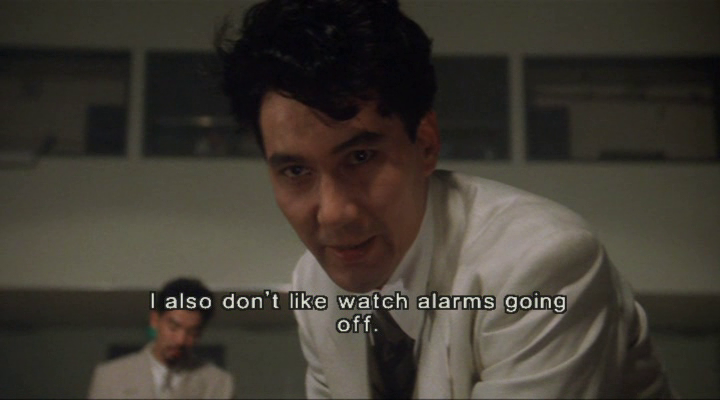

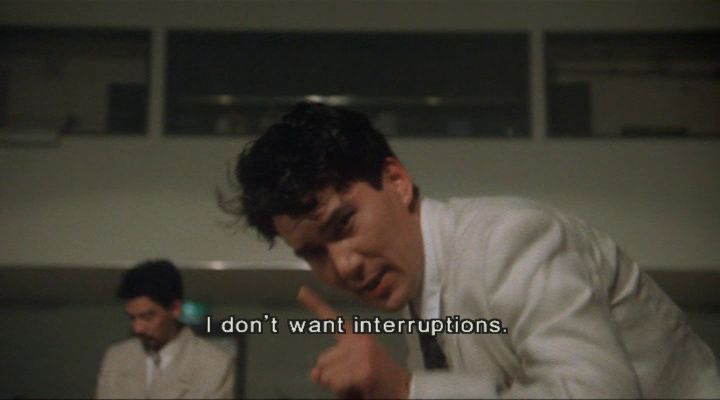

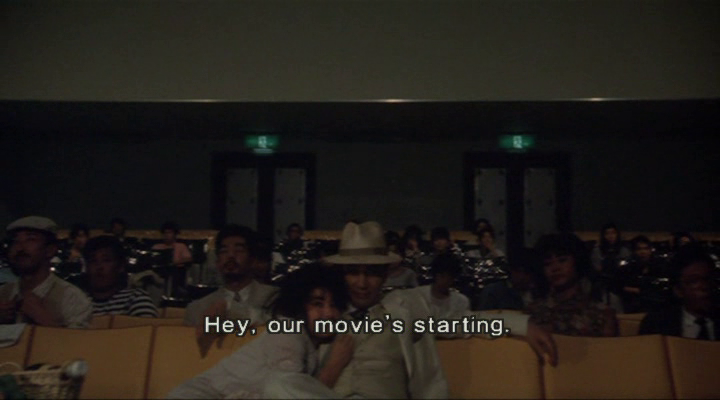

Juzo Itami was once well-known and now isn't; likewise his mentor Yasuzo Masumura. Recently, Krzysztof Zanussi's Illumination (1973) just blew me away for its philosophical depth and emotional scope in less than 90 minutes.

A very tough call, but Gloria Grahame is Gloria Grahame.